Excerpt from Submarine Cable Laying and Repairing

by H. D. Wilkinson M.I.E.E.

CHAPTER I: THE CABLE SHIP ON REPAIRS

3. Grappling.

The ship now leaves the mark buoy, and steams

out about a mile, in a course at right angles to the line of cable,

then lowers grapnel and steams back slowly up to buoy, passing

and repassing it till [sic] the cable is hooked. Sometimes the ship is

allowed to drift with wind or tide while grappling, but this is

only done in farily deep water. The speed for grappling is about

one or two knots an hour according to the bottom, and is slowest

for a rocky bottom. Cable ships generally carry various kinds

of grapnel to suit different conditions of bottom met with. The

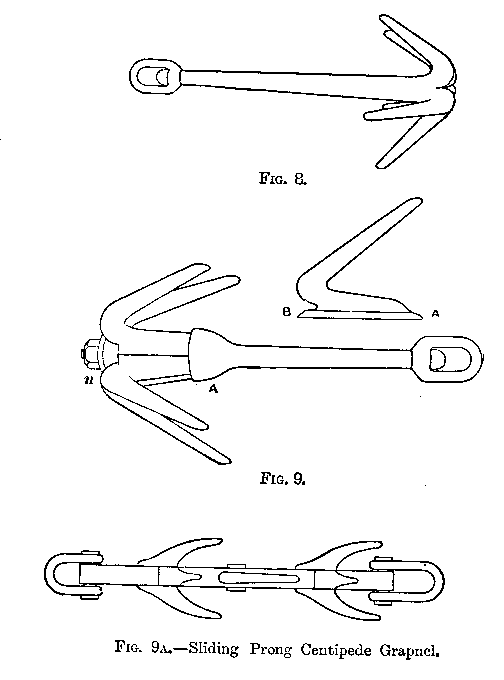

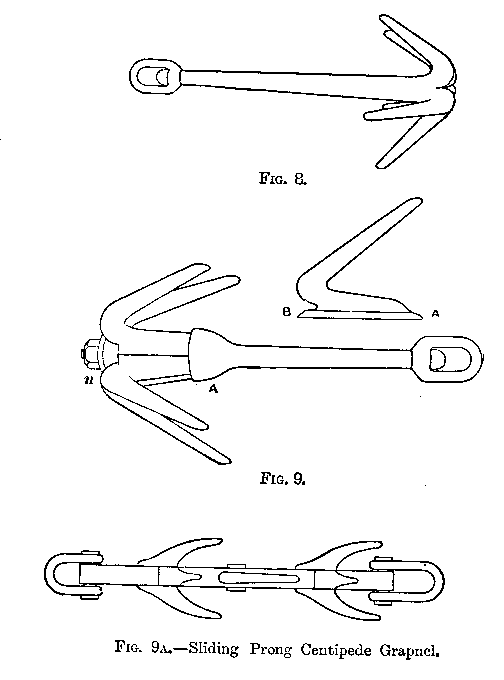

old form of 5 or 6-prong grapnel (Fig. 8) is still a very effectual

grapnel for bottoms of a soft nature, such as sand or ooze; but

meeting with any hard obstruction, such as rock, the prongs

bend down or break off. To retain the use of the shank of the

grapnel while the prongs are bent or broken off, many forms of

grapnel with removable prongs have been devised. In one of

these (Fig. 9), made by the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Co.,

the prongs fit into a hollow boss on the shank at A, and the ends at B

are all enclosed by a collar and firmly fixed in

position by the nut n. Another form, constructed by Messrs. Johnson

and Phillips, is the sliding prong grapnel, which is provided with

removable cast steel prongs of the kind shown in Fig. 9A.

By taking the shackle off one end, the broken prongs may be slipped

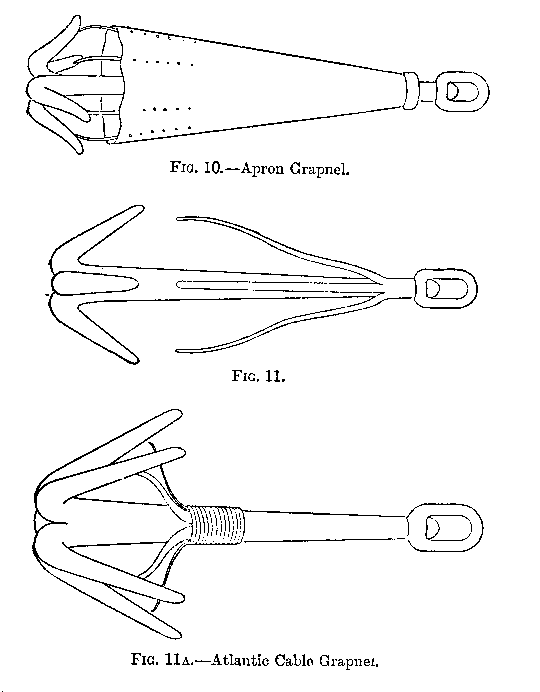

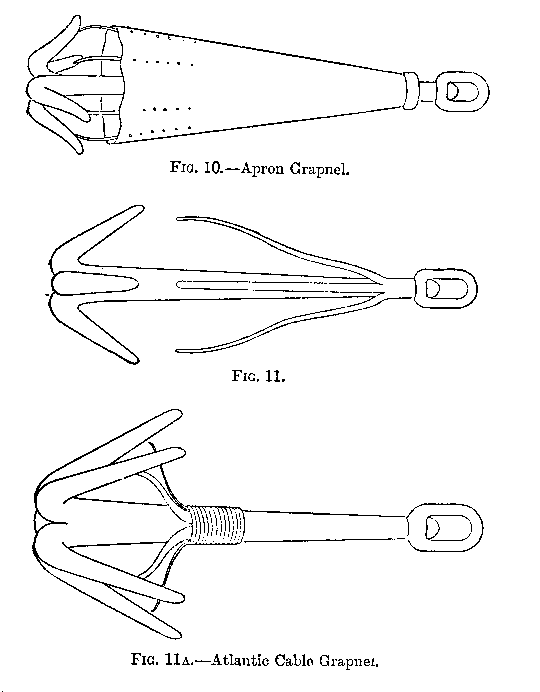

off and renewed. For rocky bottoms the Dutton apron grapnel

(Fig. 10) is frequently used. In this grapnel the apron forms a

guard for the prongs against breakage by rocks, and the opening

between the prongs and the lower edge of the apron is only a little

larger than required for the cable to enter. There are

also retaining springs from the apron to the prongs. The

grapnel in Fig. 11 has a guard for the same purpose,

made of four wrought-iron arms. These guards prevent

the cable getting out of the grapnel when it is jumping

over uneven ground. The first form of this kind of grapnel

was used in the "Great Eastern" when grappling for the lost

end of the '65 Atlantic cable. This was made by lashing five

bent steel springs, about 1+1/4in. wide by 3/16in. thick, to the stem

of the grapnel, as shown (Fig 11. 11A). It will be remembered

that the "Great Eastern" commanded by Capt. (afterwards Sir James)

Anderson, laid the '65 Atlantic cable from Ireland towards

Newfoundland, and that when about 1,180 miles from

Valentia an electrical fault developed in the cable. In attempting

to pick up and remove this fault the cable parted, the end

going overboard in 1,950 fathoms. This occurred on August 2nd

of that year, and all attempts then made to recover it

were ineffectual. But the "Great Eastern" returned in the

following year, and, after successfully laying the '66 cable,

went back to the position where the end of the former cable had

been lost, and eventually raised the end, with the grapnel described,

on September 2nd, completing the cable to Newfoundland

in six days from that date. This was the first occasion

on which a cable had been raised from a depth exceeding 500 fathoms.

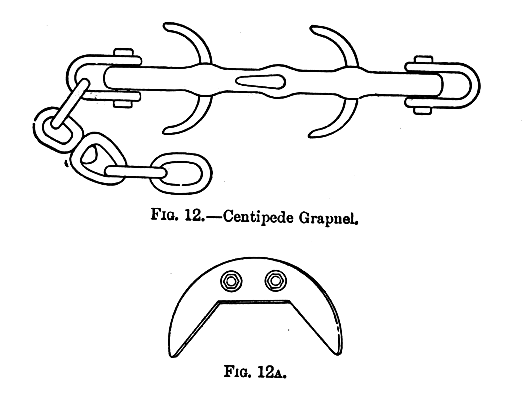

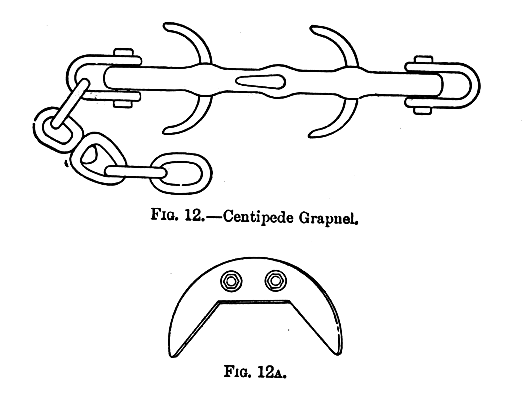

The centipede grapnel is shown in Fig. 12. One form of this

grapnel with renewable prongs is Cole's centipede. The prongs

are of cast steel, two prongs being in one casting of the shape

shown in Fig. 12A, and bolted to the shank of the grapnel.

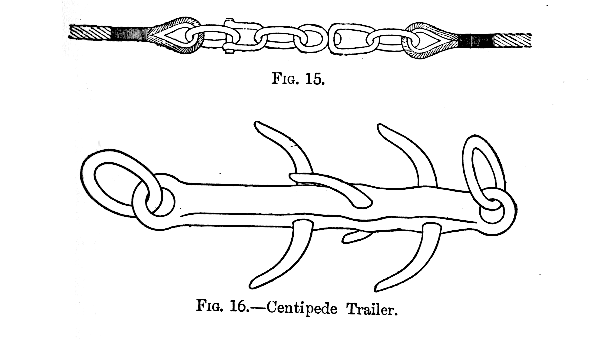

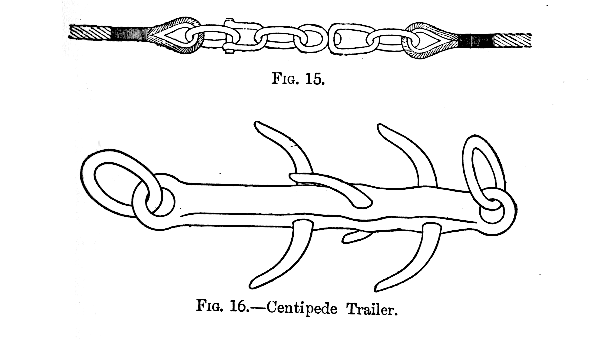

Trailers (as in Fig. 16) are used sometimes with the grapnels,

being dragged either after or before the grapnel, to keep it

from jumping, and at the same time offer a better chance of

hooking the cable. There is generally also a trailing or steering

chain attached to the end of the grapnel. This is a fathom or two

in length, and has at one end a large link, so as to

allow the other end to be reeved through it after being reeved through

the end link of the grapnel. The noose is then hauled

tight, and the chain follows the grapnel, and keeps it moving in

a straight line.

The forward end of the grapnel has usually about 15 fathoms

of 7/8in. chain attached to it to keep the front end low

as it is dragged along. To the end of this chain is shackled

the grapnel rope, which is usually a manilla rope, 6+1/2in. circumference,

with a breaking strain of about 11 tons. A length

of a few hundred fathoms of compound grapnel rope made of

six cable strands of hemp yarns, with three steel wires in each,

known as six-by-three rope, is generally shackled on between

the chain and manilla to bear the chafing against the bottom;

and this rope, for some distance near the chain, is covered with

old matting, pieces of yarn or old rope, lashed on to it in order

to form a series of raised places in the rope, which will drag

along the bottom, and prevent the rope from grazing along it,

and so wearing away. This precaution is only necessary in

very uneven grounds, as the chain in front of the grapnel is

supposed to take all the chafe. It is a common practice, however, to

put matting, &c., round the rope where it rests on the bow sheaves

to prefent chafing against the cheeks of the sheaves.

This is chiefly done when taking long drives in deep

water. This six-by-three rope alluded to is used by some ships

for the entire length, in place of manilla. The ends of each

length of grapnel rope have thimbles and links, and one end

always has a swivel and link in addition; and in coupling two

lengths of rope together, one end with the swivel and link is

used, and the shackle put through the two end links, as shown

in Fig. 15. If, then, the grapnel rolls over on the bottom

while grappling it cannot twist and cause kinks in the rope, as

the swivels between each length allow the rope to turn bodily.

4. Special Grapnels.

When working in great depths the

strain on the deep-sea type of cable is frequently the cause of

its parting. To obviate this, grapnels have been devised which,

simultaneously with hooking the cable, will cut it and hold the desired end.

This, of course, entails grappling again, unless near a total break,

but it is a more certain way to go to work, and

time-saving in the long run. When grappling for one end of a

total break in deep water, if the cable is hooked too far from

the break the strain my cause it to part afresh at the grapnel,

or if hooked too near the break the

end may slip through the grapnel in heaving

up and be lost. A grapnel of this kind,

therefore, which will

cut the cable at the moment it is hooked,

and abandon the short end

while holding and bringing up the other, is of special service

in operations where total breaks have to be repaired.

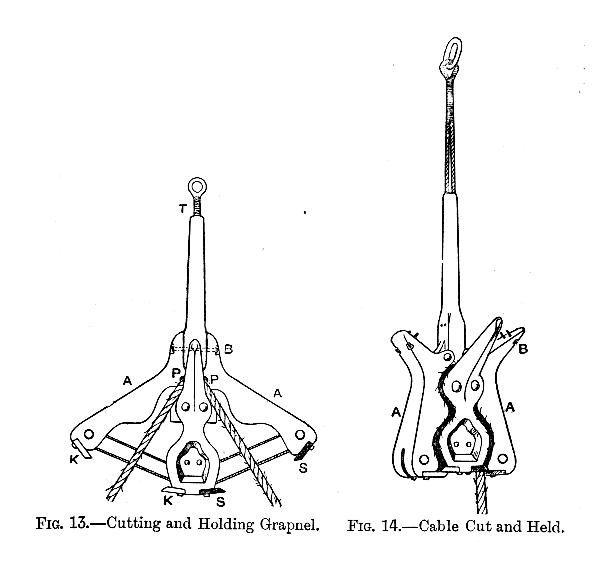

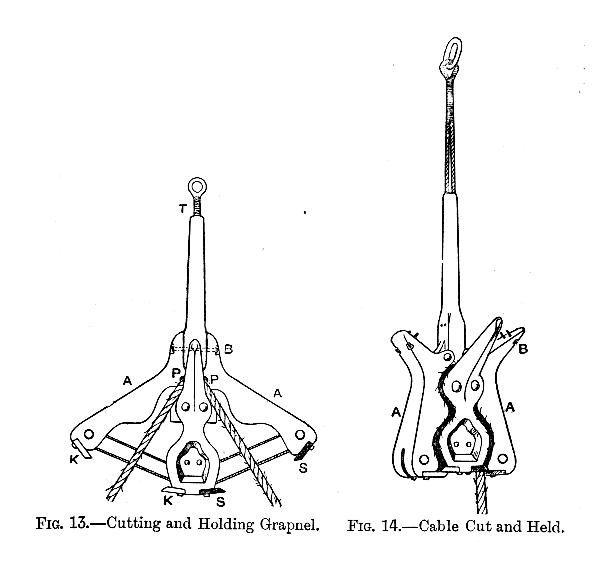

One of these forms of cutting and holding grapnel,

designed by Mr. F. R. Lucas, of the Telegraph Construction and

Maintenance Company, is shown in Fig. 13. Two arms A A,

pivoted on the pins P P, are held extended by two bolts, one

of which is shown at B in the figure. These bolts are thinned

down at the centre in the manner shown. The further ends of

the arms carry pulleys, round which a steel wire rope passes

as shown, the ends of the rope passing upwards through the

shank of the grapnel, where they are lashed together and form

the thimble at T by which the grapnel is hauled. There

are two prongs, one each side of the grapnel, and one of which

is shown in the figure. On hooking the cable, the strain on the

steel rope at T causes the extremities of the arms A A to bear

inwards with a force which causes the bolts at B to snap off at

the thin central part. The moment the bolts snap the full

force of the strain is brought to bear in clowsing the jaws,

and the bight of the cable is jammed in between the curved

portions of the arms and the central stem, as shown in Fig. 14.

As the jaws close, one pair of cutting edges, as at K K, close

across the cable on one side, and the rapidity and force of

closing cuts the cable clean through, leaving the other end firmly

gripped in the jaws. The pair of knife edges shown at

K K are on the near side, and would cut the left-hand side of

a cable hooked on the near prong, as shown in the figure.

The pair of edges S S are on the far side, and would only cut a cable

caught by the far prong.

In grappling it is, of course, only the lower prong that hooks the cable, and

supposing we are looking down upon this grapnel as it is being hauled along,

the underneath prong will hook the cable, and the pair of

edges S S will cut the cable on the right-hand side, as the pair of

edges K K are now on that side. So long, therefore,

as the grapnel is hauled in one direction with reference to

the line of cable, it will always cut the cable on the side

desired, no matter whether it rolls over or not, and will bring

up the right end. But if the direction of grappling is reversed,

the knives must be unbolted and shifted to the opposite side. This grapnel,

which has proved very successful, was used for the first

time on board the "Scotia" during the repairs of the Lisbon-Madeira cable,

in January, 1891, which it cut and brought up from a depth of 1,500 fathoms.

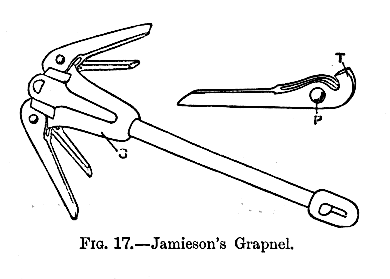

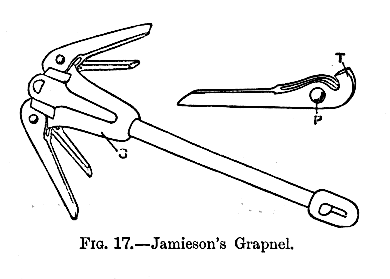

Jamieson's grapnel (Fig. 17) is designed to prevent breakage

of the prongs through coming in contact with rocks.

For this purpose the prongs are mounted on pins as at P,

about which the prong is capable of movement. The

inner end of the prong has a tongue as at T, which bears upwards

against a volute spring contained in the enlarged part of the shank at S.

When strained against rocks, therefore, the prongs give outwards, and as

soon as the obstacle is passed the internal spring acts on the tongue and

restores the prong to its position again. When the cable is hooked

the prongs do not give way, because the cable lays opposite the pivot of

the pront, or so close to it that no leverage is exerted.

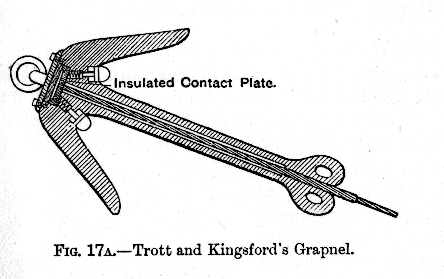

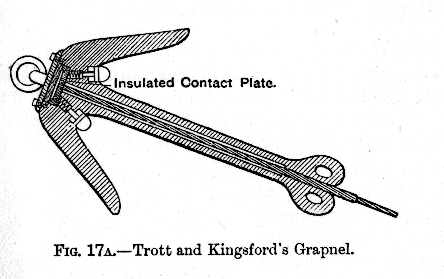

Trott and Kingsford's automatic indicating grapnel is designed to give

notice by completing the circuit of an electric bell or indicator on board

immediately the the cable is hooked.

Mr H. Kingsford described this grapnel in an interesting Paper before the

Society of Telegraph Engineers and Electricians in November 1883. The weight

of the cable, as it lays in the grapnel, causes a brass piston or plunger at

the root of the prong to be pressed down, and an electrical contact made at

the grapnel, which completes the indicator circuit

through an insulated conductor in the heart of the grapnel

rope. The plungers are pointed below, and when weighted by the pressure

of the cable force their way through a rubber disc on to a brass

contact plate.

The grapnel rope containing the electrical core for use with this grapnel

is patented by Messrs. Trott and Hamilton, and, as no swivels are used,

the rope is specially designed with a view to the prevention of kinking

consequent upon the grapnel turning over on the bottom and twisting it.

The system, which is worked with the Anderson and Kennelly patent indicator,

has been used by Captain S. Trott and Mr. H. Kingsford on board the "Minia,"

the Anglo-American Company's repairing steamer, since the year 1883,

with great success.

The illustration (Fig. 17A) shows the position of the

contact buttons and insulated plate in this grapnel; and it may be mentioned

here that should a prong become fractured or broken off, the insulation of

the contact plate will be partially destroyed, and a current set up which

can be distinguished on boardd, as it is weaker than that caused by hooking

cables. Notwithstanding the great ingenuity of this grapnel, there is

the disadvantage of requiring a special grapnel rope both on account of

the core and the fact that no swivels can be used, and it is not possible

with this rope to have it made up in sections of convenient lengths,

nor to use a

length of chain in front of the grapnel to bear the chafing on the bottom.

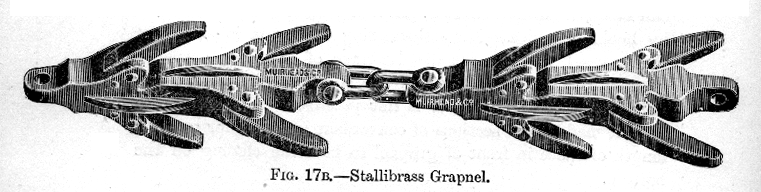

The devices described above for easily and quickly replacing the broken

prongs of a centipede grapnel by new ones have served the purpose of

limiting the very large number of complete grapnels that, otherwise,

a ship would be bound to carry, and have also effected a very considerable

saving in time. There is still, however, something left to be desired.

When a prong is broken off the grapnel generally tows with the broken

side underneath, and misses the cable, while it cannot be known on board

every time this occurs. And whether there has been a desire or not to put

to to frequent test the facility with which prongs on this or that system

can be renewed it is impossible to say, but the metal is very much skimped

in some specimens. Again, if prongs break easily, it may happen that one

on which the cable is safely lodged may break before the grapnel, owing

to slack of rope, has had time to lift, with the

result that the cable is lost. With the view of lessening these

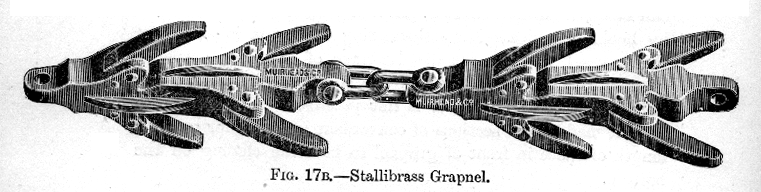

defects as far as possible, Mr. Edward Stallibrass has devised and

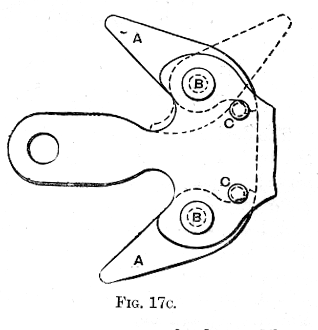

patented the grapnel illustrated in Fig. 17B, which is

manufactured by Messrs. Muirhead and Co., of Westminster, London. Normally

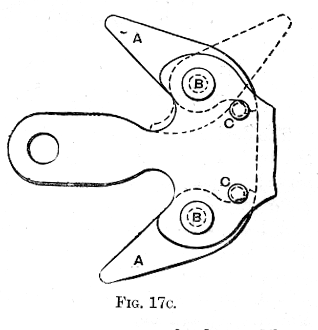

the toes A A in this grapnel are retained in position by the pins at C

(Fig 17C), but if, through meeting

with some obstruction while towing, a strain equal to three

tons is brought to bear on the point of a toe, the pin is sheared

through and the toe capsizes, turning on its pivot B to the

position indicated by the dotted lines. By this action a toe

can never get broken, and further, when in the capsized position it

projects more than before, which has the effect of canting the grapnel

over so that another toe takes the ground.

By varying the size of the

pin the toe can be made to capsize at any desired strain. The toe is

only used to guide the cable into a large rounded surface in the shank

of the grapnel, and consequently, although a toe might be capsized by a

rock after hooking the cable, the latter would not be lost. The

grapnel is made in two parts, each having four toes, and these

are shackled together, as in the illustration, or with a short

length of chain intervening. This enables it to fit better into

any irregularities of the ground, and increases the chances of

hooking a cable, besides being more convenient in other ways.

For soft bottoms longer toes are provided, and one single grapnel can

be used instead of the pair.