For a couple of weeks in August-September 2015, I sailed out of Vancouver to Desolation Sound with friends. Years earlier, Piaw and I had talked with an experienced sailor about his favorite sailing spot: Desolation Sound. Terrible name, but warm water: This sound wasn't a snowmelt-fed cold river delta, but rather nearly-still sun-warmed inlet. Warm water matters. Swimming can be fun. Sometimes, swimming is necessary. We remembered that time Jessica dove into cold ocean water off the California coast to untangle an anchor line from our rudder oh man that was cold.

Desolation Sound had potential: It had warm water for swimming, but it was on the Canadian coast. Since I like cold weather, I liked the sound of that. Everybody knows Canada is a frozen wasteland inhabited by dogsledders and curling enthusiasts; surely it would be cold enough for me. When Piaw trawled for interest in a possible Desolation Sound trip, I signed up.

(If you want to skip Vancouver-tourist stuff and get right to the sailing, go to the section titled Embarking.)

I arrived in Vancouver a couple of days early. I'd been there with Tom Lester on a road trip 10 years before. We'd spent a few hours in Vancouver; that had left me wanting more. I took this chance to play tourist.

In between the time that I'd booked my hotel and the actual trip, the New Yorker ran an article about the Cascadia fault in the Pacific Northwest that would blast the region with an earthquake more powerful than California's and how the locals weren't accustomed to earthquakes so they didn't have such great building codes. So I spent as little time in the highrise hotel as I could, instead walking around recalculating how low the chances were of a major quake hitting in the next couple of days. I chose not to think of the heat wave (ugh) as "earthquake weather."

I explored Granville Island, our boat charter place's neighborhood, scouting out a supermarket where we could buy food for our voyage. I took a harbor tour.

I walked the Stanley Park Seawall past some rocks that Astrid Atkinson had tweeted a picture of the day before.

I visited the Vancouver Maritime Museum, which had exhibits about the search for the Northwest Passage—including a preserved ice-exploring boat. I dined at La Taqueria Pinche Taco Shop, which was a terrible idea since my previous travel destination was Austin and I was still remembering those tacos well hey not all my ideas are going to be winners.

The rest of the crew arrived in Vancouver. I joined most of them at the Granville Island ferry dock; Arturo showed up as we were watching a yachter's safety briefing video at the Cooper Boating charter company. We provisioned. That night, most of the crew slept on the boat while I in one last night in the hotel. I went aboard a little after sunrise on August 25.

Who were we? As pictured below, we were

I never learned "Aunt" and "Uncle"'s names. I didn't really talk with them. They knew little English; but they knew more English than I knew Mandarin. Not aboard was Boen, Piaw and Xiaoqin's other son. Boen was back in California with grandparents.

We'd done some preparation the day before: watched a safety video, bought a week's worth of groceries. We'd asked folks at the boat charter company about sailing Desolation Sound; they didn't know much about Desolation Sound. At the time, this ignorance surprised us: why wouldn't these people sail up to the warm and sunny Desolation Sound every chance they had? (Later on, we'd figure out that it was easier to motorboat around Desolation Sound than to sail there; and while Vancouver was the nearest place to charter a sailboat, there were closer motorboat charter places—no doubt, people working at those nearby places knew Desolation Sound well.)

Up in the main salon, most flat surfaces were covered with containers of food. This gave me the heebie-jeebies. I was used to monohull sailboats, which heel over (tilt) a lot. I imagined the first direction change would tilt the boat and send all this food tumbling to the floor. I needn't have worried. This sailboat was a catamaran, and thus had a wider base than a monohull did; it wouldn't tilt much. Our food would stay in place just fine.

But everything was not fine.

The boat was outfitted with overengineered gimmickry that broke. E.g., the salon (the room with all the food) had a table+bench that turned into a bed. The table had telescoping legs; they shortened to lower the table down to bench level for sleeping; when you were done sleeping, hydraulics in the legs eased raising the table back up into position. Except something was wrong with the hydraulics: they wouldn't let you lower the table; they weren't raising the table; they were just in the way. Elsewhere, some wiring had come loose. Aubrey, the nice lady from the boat charter company fixed what she could that morning. We got the table into shape so we could raise and lower it without being stymied by hydraulics. Aubrey fixed the wiring.

Those of us who weren't fixing things waited around. Arturo and Bowen played a game in which they stole each others' body parts. It was like "I've Got Your Nose" in which the conflict had spilled over into neighboring territory.

The boat was ready. Well, ready enough. Was the crew ready? Sort of. E.g., I remembered that I wanted to get rope on and off winches in a way that didn't risk entangling my fingers—but I didn't remember how to do that without looking. I was rusty.

And some of us hadn't been sailing at all. Not just rusty—plain ol' ignorant.

But the boat was ready! It was time to head out. We cast off lines. Piaw motored the boat away from the dock. He was glad we were on a catamaran. A catamaran has two motors, one at the rear of each hull. This gives the pilot more control than a one-motor boat. If you want to turn tightly, you can have one "corner" of your boat motoring ahead and another "corner" holding steady.

But some of us weren't used to sailing at all. One of us had headed onto land to use the restroom (smart) and hadn't told anyone else (normally oversharing TMI, but in this case a bad idea). Sooo the boat headed out into the water with someone still ashore. We figured this out after a few minutes. Those two motors helped Piaw turn the right boat around so we could head back to the dock.

It was nice we had an excuse to head back: Aubrey-the-nice-lady-from-the-charter-boat-company had left her phone on our boat.

But eventually we were all on the boat and then we headed back out away from the dock and onto the water for reals this time. We motored away from the harbor and out into the channel that connects Vancouver Harbor to the straits and ocean beyond.

There, the sailors shook the rust off of their sailing skills. We Keystone-Kopsishly figured out which lines were connected to which sails. (Stymied for a while because the main halyard was not connected to any sail; we were supposed to connect it ourselves.) There were electric winches; instead of turning a crank by hand, we could just press a button. Still, we were slow to bring the boat about at first. Lines tangled. We couldn't find the right lines. We got closer to bumping an anchored containership than you'd like.

Was there a reason our ladder was hanging down into the water behind the boat? Was there a good reason? Nope, we secured the ladder.

I yelled at the jokers on the other side of the boat to stop pointlessly running the electric winch next to my head—but then they pointed and I looked at where my hand was resting and I saw that I'd accidentally started that winch myself, just by leaning. Stupid convenient electric winches.

We did de-rust our skills and we did sail for a bit until we were able to go where we wanted and turn without minutes of yelling.

But some of us weren't used to sailing at all. Little boy Bowen headed up to the front of the boat. Piaw hustled after him. When I heard the anchor clank, I hustled after both of them. Bowen was just three years old, but apparently that was somehow old enough to figure out how to untie the anchor. The anchor and its chain clankily started to head down into the water. The anchor didn't fall far before Piaw stopped it. But we still wanted to haul it up and make sure it was better secured this time.

We admonished Bowen to be careful and made ready to haul the anchor back up. Piaw pressed the button for the electric winch. I watched the anchor chain to make sure nothing went wrong—but was surprised when Bowen reached forward to grab the moving anchor chain. Hadn't we just told him to be careful? Of course, we aren't born knowing what it means to "be careful" in any given situation. I knew that heavy clanking metal chains are no place to put delicate little fingers; but I probably learned that by getting hurt a few times.

Fortunately, Bowen didn't get hurt. I don't know how he avoided injury, but I'm not complaining. I don't know if he learned not to stick his fingers into moving clanky big chains. I know I learned to keep an eye on Bowen, knowing that he'd blithely hurl himself into the path of destruction with no warning. So that was a good lesson.

By the afternoon, we had made it as far as Snug Harbor on Bowen Island. With someone named Bowen aboard, you bet we wanted to visit Bowen Island. And they had space in their harbor, so we rented some dock space.

We explored the marina area. There was "Bowen Island" signage to photograph Bowen next to. There was the recommended Tuscany Pizza—which was closed, since it was still afternoon. So we ate at the Old Orchard Grill instead, and that was fine. Some of us took a little walk around, saw a big pond with lily pads and a beaver dam and such. It was nice to sleep in harbor, where there were showers and toilets on land.

The next day, there wasn't much wind. This was pretty typical for the region—offshore islands shielded us from waves and wind. They shielded us from the wind so much that sailing would have been at a snail's pace. Instead, we motored north.

This made for smoother travel, but not so interesting. We set a course on the autopilot and went. Someone sat at the wheel to keep an eye out for obstacles (e.g., other boats) and steer around them. I sat for a while; the main challenge was staying focused enough to keep checking for obstacles.

Folks who weren't steering passed the time. We talked, we prepared food, we ate, we read. Arturo and Bowen stole each others' body parts. Bowen drew on whatever paper was handy. Right now, I'm trying to read my notes of what we did this day; it's a little tough because Bowen was scribbling over them for a while.

We made good time. We were trying to figure out where we might dock that night. About once an hour we'd project ahead, and we kept on pushing our estimate further north.

We discovered another piece of overengineered gimmickry on the boat. We had two heads, i.e., two restrooms. One had a normal marine toilet, worked by a simple hand pump. But one had an electric pump. This pump wasn't working; it made noises and ripples; but failed at moving icky things out of the bowl to the holding tank.

In this lovely modern age, a just-off-shore sailor can communicate by mobile phone. Piaw got on the horn with the boat charter company about the broken head. They said they had some facilities in Powell River, a big town further up the coast. If we pulled in there this afternoon, they could send someone to repair our head. So we headed to Powell River.

On our way there, I got volunteered to take a shower. We hadn't tried out the boat's showers yet—we'd stayed at marinas with onshore showers. But considering how many things had gone wrong with systems on this boat, Piaw wanted a test before the plumber showed up. The shower worked fine. I was kind of grumpy to take a cramped sailboat-bathroom shower instead of a spacious land-bathroom shower, but the risk of spending days with steadily-stinkifying folks justified it.

Powell River marina had space for us. We refueled, pulled into our space (helped out by nice neighbors who caught and tied up our docklines). We took care of things on land. Arturo and I headed uphill to the supermarket to get some fresh groceries. Other folks did other things. Someone from the charter boat company showed up and wasn't able to fix our over-engineered over-complex electric-pump head. Good thing we had another head.

As we prepared and ate dinner, much of our conversation was about the priorities of the folks who had outfitted this boat. Scant storage; strange love of fragile gizmos. Were they day sailors, always close to their home marina?

We motored out of Powell River at sunrise. The scenery was pretty great.

There was a really shallow passage with one deeper route through it. We watched another boat make its way through and used the same path. It was good to be in popular waters.

We reached Desolation Sound. Specifically, we reached Tenedos Bay, a sheltered anchorage. There were other sailboats anchored here. A couple of boats were motoring out just as we were arriving. This was a good thing about having set out at dawn: we arrived just as more sensible travelers were setting out, and thus "parking spaces" opened up for us.

This was a popular anchorage. If we'd been there a couple of weeks earlier, it would have been much more crowded. We were on the tail end of sailing season; thus there was space, albeit still with plenty of boats around.

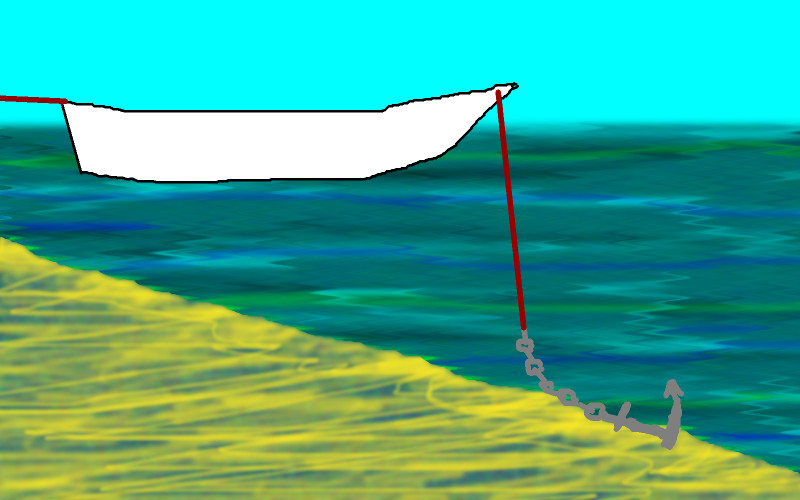

The bottom was steeply sloped; though it was shallow enough for an anchor line close to shore, it was pretty deep at the center of the bay. For these reasons, we would try something new to us:

We would try stern tying. We'd drop anchor close to shore. Then, using a dinghy we'd run a line from our boat, hook that line around a tree and back to the boat. We'd be tied to shore as well as anchored. Piaw explained the two reasons this was a good idea. If you anchor without tying up to shore, your boat swings around in a circle over the course of the day. As the tide shifts, the current pushes the boat in one direction then another.

We'd never done this before. But the theory was straightforward.

We lowered the dinghy, lowered the anchor, bridled the anchor. I clambered into the dinghy carrying a reel of rope and my sandals. The rope was on a reel; I'd thought I could put on my sandals in the dinghy while letting the rope unreel on its own. But that was an ignorant guess—the reel didn't unwind so smoothly. Worse, the rope would have tangled Arturo and/or a propeller. Instead of handling my sandals, I played out the rope.

So when the dinghy bumped up on land, I still didn't have my sandals on. I wanted my sandals on. This part of the land was rocky. Shellfish (oysters? clams?) lived on these rocks; sharp shells abounded. I crept onto land. I hauled the reel of rope, hooked it over an old log to keep it stable while I put on my sandals. But remember: the reel didn't un-wind smoothly. When the sailboat drifted from shore, the line dragged the reel over the log. The reel bounced towards the water. I did a quick hop over the log, caught the reel, pulled in the line's slack so it didn't tangle a propeller.

Something had brushed my legs as I hopped after the reel. As I put on my sandals, I saw that I'd scratched my legs on sharp shell shards. Eew. No time to deal with that: I had figured out that each minute I prolonged this process was another minute for things to go wrong.

I crept up above the rocks to the dirt, where trees grew. There were trees and plenty of undergrowth. It took a while to figure out a tree to hook the line around where it wouldn't just get tangled in branches and bushes. (And, as we'd find out when it was time to leave, I didn't do a great job of that.) I carried the line back to the dinghy. Arturo motored us back to the sailboat; again, some line-handling to make sure the line didn't tangle a prop or knock Arturo over or whatever. Then we were back at the sailboat and tied the other end of the line to our stern. We were stern-tied!

My legs had been oozing blood for much of this process. Those scratches went deeper than you'd expect—the shells had been sharp. Fortunately, once I rinsed away the blood, the scratches had stopped bleeding. I set about bandaging up my feet. As I write this a month later, faint scratches still adorn my right leg.

During our dinghy adventure, we'd found out that Desolation Sound's water was not as warm as reported. Instead, it was cold as you'd expect. So we weren't so sure we wanted to walk to Lake Unwin. Guidebooks said it was nice for swimming. But how far did we want to trust reports of good swimming? Still, there wasn't anything better to do, so we set out.

We all piled into the dinghy. Arturo motored us out of Tenedos Bay to a nearby beach. There, we hopped out of the dinghy (stepping in the cold water), and clambered up onto the beach. We tied up the dinghy to a rock (taking some care because the incoming tide threatened to put that rock under water and perhaps lift up our line).

We walked through some woods, saw a bear, did not get eaten by the bear, found the lake, found a bit of shoreline that wasn't already occupied by other visitors, and set about swimming. The water was cold-ish. But it wasn't so cold as to make one worry about hypothermia, so we were soon paddling around. We'd been promised swimming, by golly, and we were going to swim.

We made our way back to the dinghy, untied it from its now-underwater rock. Arturo motored us back to the sailboat.

There was plenty of wind that night, but we were in a pretty sheltered spot. We were glad we'd taken so much care with our anchoring. One of the boats in the anchorage was perhaps not so well anchored—during the night, they repositioned themselves. To do so, they turned on all their lights. This woke up all the other boat captains, who started turning on all of their lights and double-checking everything to make sure their anchorings were secure. I mostly slept through this.

It's no fun to re-anchor at night in a bay with the only lights being those on your boat. I sure am glad we didn't need to do that.

The next morning, we set out for another part of Desolation Sound,

Prideaux Harbor. It wouldn't be as sheltered as Tenedos Bay, and some

wind and rain was in the offing. Then again, when we'd swum in Lake Unwin,

we'd pretty much done everything there was to do around Tenedos Bay, so it

was time to move on.

It was pretty scenic, much like the San Juan Islands; not so surprising since we weren't super-far from those.

When we reached Prideaux Harbor, it (and nearby harbors) were crowded with boats. We putt-putted around, looking for a good place to anchor. The nicely-sheltered spots were all full; we ended up at a not-so-sheltered spot that at least had a nice view.

With rain predicted for the next day, it made sense to go expeditioning right away. Once we were parked, we piled into the dinghy and Arturo motored us about. We'd heard there was another swimming area around here, a sun-drenched lagoon. We beached the dinghy, tied up to rocks on shore, went over a hill, and sure enough, there was the lagoon.

The ground around the lagoon was rocky; shells grew on those rocks, the same kind that had scratched up my legs the day before. I took my time walking; I didn't want to give those shells another chance at me. When Xiaoqin warned Bowen to be careful, I told him that the shells had messed up my legs yesterday.

Folks started to get into the water. Then Xiaoqin cried out. Bowen had fallen, and a shell had cut his leg. We carried him up, away from rocks and sharp things. His leg was covered with blood, but I knew better than to worry: my leg had been covered with blood, but that blood had seeped from little scratches. But I should have worried: wiping away the blood revealed a deep cut. Fortunately, Arturo had NERT training. He set about binding up the wound. But that wasn't going to be enough: Bowen would need stitches. None of us knew the right way to stitch someone up.

And so we made our way back to the dinghy. We putt-putted back to the sailboat. It felt agonizingly slow. But eventually we were back to the sailboat.

Some folks set about doing a better job of cleaning and covering the wound. Piaw got on the radio, asking if any of our neighbors were doctors. With this many yachters around, was it too much to ask that one of them be a doctor?

But the first voice to answer wasn't a doctor. Instead, it was the Canadian Coast Guard. They had Piaw call on his mobile phone so he could get in a conference call to arrange Coast Guard pickup and an ambulance.

So we waited an hour for the Canadian Coast Guard Ship Cape Caution to come find us. The hour felt long. Of course, it was much quicker than the time it would have taken us to motor (or sail) to civilization. We took some time to make ourselves ready. We knew that as soon as the Coast Guard took Bowen and Xiaoqin off the boat, we'd want to head down to a civilized marina taxi-able to the hospital.

A neighbor motored up in a dinghy. They had a first aid kit if we needed one. (We didn't need one.) We asked them for advice on the closest taxi-able marina. They pointed us at Bliss Harbor. They motored off. (Fortunately, when the Coast Guard showed up, we asked the same question. They warned us that Bliss Harbor was only connected to other places by a dirt road; they told us to head further south to Lund.)

The excellent coasties of the Cape Caution motored up, tied up

along side, took Bowen and Xiaoqin aboard, and motored off. Those of us

still on the sailboat hauled anchor and set off.

There wasn't much to do for those hours of motoring. But this time, it didn't feel boring. We headed south, eventually reached Lund. A hotel there had some space on their dock, so we rented it. Xiaoqin had phoned us: it the time it took us to motor down, the Coast Guard had brought her to civilization, Bowen had been ambulanced and hospitaled and was stitched and bandaged; she was riding a taxi up to Lund to meet us.

So now the rest of us were just waiting, but it was no longer an agonizing wait. Lund was a quaint little resort town. Its claim to fame: it was the start of the Pan-American Highway, known in the USA as Highway 101. We ate a tasty dinner at the Boardwalk Restaurant, serenaded by a bagpiper. Leaving the restaurant as we got there: the crew of the Cape Caution. As we headed back to the boat from the restaurant, our phones got back into a signal-y area and thus we found out that Xiaoqin and Bowen's taxi had made it back; they were at the hotel coffee shop. Piaw bundled them over to the Boardwalk just before it closed. Eventually, we were all reunited onboard the sailboat.

The next morning, we didn't set sail at dawn. We didn't set sail at all. Stormy weather was predicted. I was pretty tired out from the previous day's excitement; and probably other members of the crew were, too.

There was rain predicted for the next day, too. But there were some clear hours predicted. And we were rested up. And it was time to head south if we wanted to see things on our way back to Vancouver.

The next morning, the weather was clear; but stormy rain was predicted for the afternoon. Thus our plan: make some southward progress in the morning, make sure we were in a sheltered marina by the afternoon.

Though it wasn't storming, the water was still choppy from the previous day's weather. We motored out. We did some sailing. The boat was sloshing around more than it had been. To save ourselves some tacking back-and-forth, at one point we sailed beyond the protective layer of islands, in more open water. This was even rougher. Things did not go well for the not-so-experienced sailors. Once the experienced sailors figured this out, we struck sails and resumed motoring in relatively-calm-but-still-choppy waters.

At mid-day, we were close to Lake Powell's Beach Garden Marina, a marina attached to a big hotel. We arranged to stay there for the night.

Though the weather was windy, it wasn't very rainy. So we went for a walk in the neighborhood. There were blackberries. There was a frou-frou food market. The hotel itself had a heated pool; most folks went swimming except Bowen, with his bandaged wound; and me, still unable to function in heat.

By the time the next barrage of rain hit, we were back on the boat.

The next morning, the rain was not so bad. But it was there. And the water would probably still be choppy from the previous day's storm. Half the folks onthe boat had been queasy yesterday. How much more of this could they take? They could probably endure more, but would likely be grumpy. What were our options?

Piaw spent the morning on the phone with the charter company, figuring out which of these options were real. The charter folks were willing to hire a skipper to bring their boat back. (That was nice of them; I assumed we'd have to pay for all or half of this.)

There followed a whirlwind of activity. Packing our belongings into luggage. Booking a flight to Vancouver. Booking rooms in Vancouver. Throwing out food that wouldn't handle being packed up in luggage. (Sadly, there was a lot of this.)

Taxis to the airport. In the airport waiting room, Piaw and Arturo figured out a road trip to an especially nice fjord they wanted to see. Instead of sailing there, we'd drive a van. Flight to Vancouver. Train from YVR to downtown. Walking through downtown in the rain with luggage to the hotel. And then we were in.

We lunched at the International Village mall food court. Strolled through Gastown. Walked past Secret Location; with that name, it should be the destination of every Vancouver puzzle hunt.

The next day we played tourist in Vancover some more. We caught a bus to Stanley Park and walked about. We visited the aquarium; we studied its exhibit on the Sechelt Inslet, which we still hoped to road-trip-visit.

We caught another bus to Queen Elizabeth Park and visited the Bloedel Floral (and tropical bird) Conservatory dome. There, signs warned us not to use selfie sticks, which upset the birds(?). We caught the train down to Richmond, where we dined at Shanghai River Restaurant. There, I wasn't sure if the little food bits clinging to the string beans were mushroom or pork-for-flavor. Fortunately, they slid right off so I didn't have to figure out whether my digestive system would react.

We packed up our things and stored them in the hotel's back room. We piled into a van. Arturo drove us through the rain along the highway to Horseshoe Bay, a ferry port. (Were you wondering why we caught a plane from Lund to Vancouver instead of a bus though Lund is on Highway 101? Once you're far up north, Highway 101 gets interrupted by ferries.) We got there kind of early to get in line to make darned sure we made it onto the ferry; we had to be at a dock in Egmont on time. Fortunately, the ferry line setup in Horseshoe Bay lets you hop out of your vehicle and wander around town for a bit of snacking and such. So we did that.

The ferry ride to Langdale took us past Bowen Island and was otherwise without anecdote.

Then we continued along the drizzly Sunshine Coast Highway, pausing for lunch, until we arrived at the Egmont Marina.

We'd asked a boat tour company if we could take their tour to Princess Louisa Inlet. They already had a boatload of people for the day. Fortunately, there were a boatload of us, so they set up an extra afternoon/evening outing for us. We arrived at Egmont Marina just a few minutes before the previous tour pulled in.

The boat tour was educational and exhilirating. We saw seals. We saw petroglyphs. We learned some local history. The exhiliration came when I stepped out of the cabin and out onto deck. Being outside on a speedy boat in the rain feels amazing, uhm, if you were raised in cold and damp. I noticed that the other folks were pretty glad to stay in the enclosed cozy cabin.

We saw plenty of debris in the water. Back when we'd been plotting out our sailing route, we'd thought this would be a good area to explore during storms, since it was so sheltered. But during the storms, this inlet had experienced waterspouts. At a nearby marina, the wind had picked up a boat and smashed it into the dock, damaging both.

Eventually, we made our way through inlets and amongst fjords until we reached the base of Chatterbox Falls.

Princess Louisa maritime park has a dock at the base of Chatterbox Falls. With the boat parked at the dock, we took a little walk through some lush rainforest (complete with rain) to the falls. I couldn't help but laugh, the roar and mist was so powerful.

We fooled around a little, and then it was back to the boat for the ride back.

There was more to do there that we skipped: a two-hour unmarked, unmaintained trail up to some place called Trappers Cabin. Then again, taking on such a trail in the dark and rain probably counts as a bad idea.

Night fell as the boat hurried back. And then we were back at the marina. Back in the van. Into Egmont, found the lodge where we had a reservation. We cooked a simple meal of sandwiches and soup made from packets. (I thought fondly of some of the lovely ingredients from our boat that we'd had to toss out; I don't think I was the only one.)

The next morning, we hopped in the van and drove south again. This time, we stopped at more places along the sunshine coast. We heard about storm damage—not huge, but enough to make us glad we'd been in a snug harbor before.

And there was more road and a ferry ride, and we were back in Vancouver.

We stopped by the base of Grouse Mountain. There's a cable car up to the views at the top. But Piaw thought to ask what the views were like: they were obscured by clouds. Today was not the day for Grouse Mountain.

We went to the Maritime Museum, a place where we could clamber around on a boat and yet stay out of the rain. There was a bit of that. And then I brought Bowen to the museum's playroom, where there were toys—except I didn't really. Instead, we digressed into a big empty banquet room in which we chased around. I guess Bowen wasn't old enough to know that toys are more interesting than a big empty room. Chasing around was fun, though, so maybe he was onto something.

We went our separate ways; Arturo dropped us off. First, most folks at a hotel where they'd sleep before making their way back to the states. Me at my hotel. Arturo drove to meet his brother who'd just flown in so they could take a road trip to the Cascades.

For the next day and a half, I walked.

I walked False Creek and the Sun Yat Sen Garden and Main Street.

Main Street had the Regional

Assembly of Text, which had printed stuff including a library of 'zines.

It was a reading library, and I didn't want to spend my Vancouver time

reading, so I didn't have as much fun there as you might expect. But I

had some.

I walked in Richmond, a suburb. When reading about the Cascadia earthquake zone, I'd learned that Richmond's below sea level in places, surrounded by a raised earth wall. The wall reminded me of Galveston: this raised road along the shore, waiting for the next disaster to let in the waves.

I visited a couple of gardens (and other things) at UBC, too.

Then it was time to fly back to San Francisco where the tacos were OK but the Mission-style burritos were the best.